Written by Andrea Eaton for the 5th Annual Long Island CRPS Awareness Walk & Expo

Five years ago, I was diagnosed with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), also known as Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome (RSD). I was playing airplane with a 4-year-old. Two other children wanted to play as well, so they jumped on top of us. In that moment, I had two choices. I could allow the children to fall and potentially get hurt or break their fall. I chose the latter and ended up dislocating my elbow, breaking my radial head, tearing my tendon and both ligaments.

It was the most excruciating pain I ever felt.

I went straight to the ER where they knocked me out and relocated my elbow. I was not able to move, bend or straighten my arm. The orthopedist couldn’t believe the severity of the injury. He told me I may never have full range of motion of my arm again, and my response was, “watch me!”

I had to take a leave from my job as a kindergarten special ed teacher as I was physically unable to do my job. I went to physical therapy three times a week for three hours a day. The therapist would literally sit on my arm to make it bend and straighten until I cried. I was so determined to be ok again I was willing to do anything. It took four months of hard work and an elbow manipulation to break up scar tissue to reach my goal of finally having full range of motion back.

During that time, I had also gotten into a car accident and began physical therapy for my shoulder and neck. When I went back to the orthopedist, he told me all was healed, but the pain was still there; it was even worse than the day of the accidents. A little puzzled I went for a 2nd, 3rd and 4th opinion until finally I was sent to an elbow specialist at Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS).

After examining me, the doctor sent me to a pain management specialist who diagnosed me with CRPS. The burning, numbness, deep, sharp bone, muscle and tissue pain was/is unbearable. My skin felt/feels like it was/is paper thin and the mere touch could send me flying. I was affected from the tips of my fingers up through my shoulder blade and into my neck. It is so bad in my hands they almost always feel like they are on fire, literally. I went into a pretty bad depression, not being able to work and getting a lot of slack from my job. Very few people or doctors understood; I felt so alone and hopeless.

I ended up on countless medications and started getting sympathetic nerve blocks and spinal epidurals every month for a year. Things started to look up and I was going to be able to go back to work. Then in late August of 2019, I was crossing the street and I was hit by a bicyclist riding up the wrong side of the road. He came from behind a parked van and neither of us saw each other. I was thrown into the middle of the street and fell onto the left side of my body. Sure enough, because that’s the nature of CRPS (it spreads from further injury), it not only worsened my arm, neck, and shoulder; it spread to my lower back. I was not able to use ice to help with the pain and inflammation, because that too makes CRPS spread.

That was a hard lesson I learned at physical therapy. I always felt so much worse after icing my arm, and never understood why, until I did more research. I then began physical therapy for my back as well. I basically lived at my therapist’s office. I started getting more epidurals and sympathetic nerve blocks, but to no avail. I tried to go back to work, but the pain was so bad, I couldn’t manage. I wasn’t able to sit, stand, reach or bend for any period of time without excruciating pain. I felt isolated and misunderstood. I always knew/know it’s not anyone’s job to understand what I was/am going through, but it hurt that so many didn’t even try.

It was easier to judge me than to try and understand.

I looked perfectly fine as CRPS can be an “invisible disease.” I ended up taking another leave and opted to get a spinal cord stimulator implanted in my spine and my hip, which is a major surgery. It took 10 weeks to heal in any capacity. I also had a radio frequency ablation and a medial branch block performed. Unfortunately, each procedure only made my CRPS spread. It went up into my head and face, down my spine, across my back, butt, down my leg, into my feet and toes as well as internally into my abdominal area. I was (am at times) a complete mess. The hardest part was and still is, there aren’t many or any doctors that understand or really know how to treat CRPS.

For any of you who watched the Netflix documentary, “Take Care of Maya,” you saw first-hand how misunderstood and debilitating this disease is. CRPS presents itself very different in each individual making it so difficult to treat and diagnose. So many doctors think it is all in your head and you are making up the pain. They cough it up to anxiety; leaving you angry, confused, unseen or heard. By February of 2020, I had no choice but to go back to work because I used up all my allowed leave time. I would have lost my health insurance and that was and still is my life line. Because of the nature of my job, I was reinjured by a child in my class. This caused me to go out on another leave after only a month and a half of going back to work. Because the injury happened on the job, I was given two weeks leave. It happened two weeks before the pandemic began and schools were shut down. I was then able to work from home and keep my health insurance. During that time, like so many others, I was unable to get the treatments or physical therapy I needed; only making my condition worse. I dealt with a lot of anxiety, depression and PTSD to the point that I ended up being hospitalized for a short period of time.

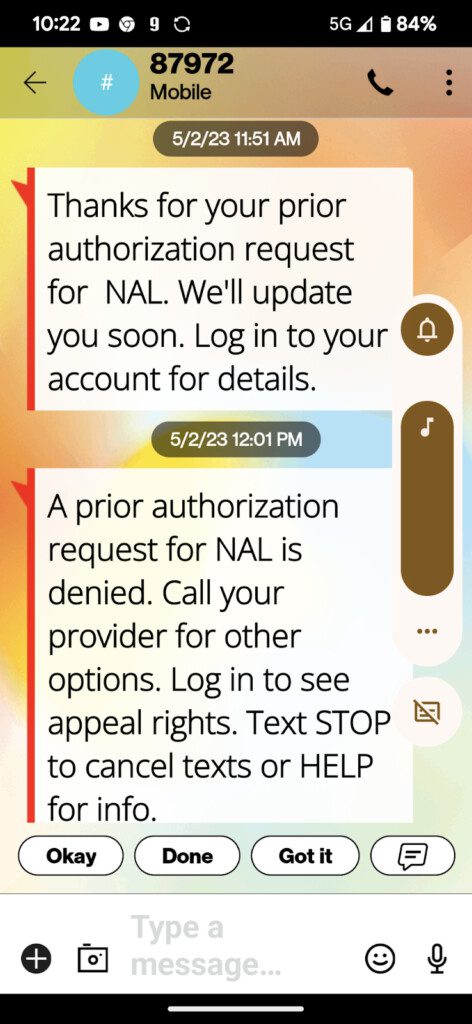

CRPS is known as the suicide disease because there is no cure, flare ups are constant, medications and treatments are very short-lived leaving so many people hopeless. Insurance doesn’t cover most of the treatments that actually work because so little is known about CRPS and the research isn’t there. In September of 2019, I continued to work remote as a kindergarten special ed teacher. It was one of the most challenging and rewarding years of my career.

In May of 2020, I had to get my spinal cord stimulator removed because my body was rejecting it. It was causing more pain than helping at that point; it just continued to spread. I have/had done so much research on CRPS and found how ketamine is a game changer to help with the pain. I also found that it is necessary to stop the spread of the disease whenever having a procedure. A procedure as simple as filling a cavity to the most invasive of surgeries. Ketamine stops the pain receptors in the brain and basically tricks the brain for the time being out of pain. I wish I had known about ketamine or had been informed by my doctor when I had the spinal cord stimulator implanted. I know it would not have spread so badly after the first surgery.

The removal was very successful with ketamine, no spread, but unfortunately pain again increased to unbearable proportions. My mental state was also very affected by the ketamine due to the large amount given during the four hour surgery. I was in a “K hole” as they call it, for about three weeks. It was one of the scariest feelings I have ever experienced. I didn’t think it was ever going to wear off. In September of 2021, I was thankfully able to work remote for one more year in an office position. At this point, I was grasping at straws. I was trying everything to find a doctor that could help me. No one seemed to know enough about the disease and didn’t know where to send me next. I had seen dozens of doctors with no resolution. I was seriously loosing my mind from the pain, isolation, ER visits from the pain, recurrent ketamine use and trying to learn how to be a person I didn’t want to be; accepting something I didn’t want to accept. I have always been so active and adventurous, and all of that had/has come to an end, period.

In August 2022, I went to Holistic Centered Treatment Center in Idaho to try another way. I met an incredible Doctor, Traci Patterson. She truly changed my life. I was there for three weeks and learned how to calm my nervous system and vagus nerve, which therefore lowered my pain levels. There are people, like Dr.Traci that were/are able to go into a remission. I unfortunately am not one of them… yet. I continue to work her program at home as well as to fight this horrible disease, because that is who I am and always will be.

In October of 2022 I received disability retirement from the New York City Department of Education. It was a very bittersweet day for so many reasons. Anyone who knows me knows how I adore and connect with children. Knowing that I couldn’t do my job anymore was a very hard pill to swallow, considering all that I had to take! To think of being retired at 41 years-old is mind boggling. These have been the most challenging years of my life, and if you know you know, I’ve had challenges!

I know I could not have gotten through any of this without the love and support of my fiancé Alan, who is my biggest cheerleader, researcher, nurse, therapist, caretaker and best friend. My family and friends have also been my sanity and my rocks. I have made many friends along the way from different support groups and involvement in organizations like [RSDSA]. They continue to help me to understand myself, my body, my mind and how it is all affected by this insane disease.

I have hid from this disease for so long because I have felt like it defined me. I have been so embarrassed of this person I have become. It feels like I’m living in someone else’s body and mind. I am here now sharing my story, not for sympathy, but to spread awareness, help others going through a similar situation and remind us all that life can change in an instant.

When we search deep down inside ourselves, we can truly find the courage to take on life’s challenges. I am not always able to do this with grace and I’m doing it. There will always be scars, physical and emotional, good days and bad days. There are days and weeks I’m stuck in bed from the pain, exhaustion, depression, anxiety, brain fog and flare ups. It’s the good days that I work toward and look forward to. You may see me dancing and having a great time and wonder, “how is she doing that, she must not be that sick.” I’ve gotten the, “you don’t look sick,” more times than I can count. It hurts to hear and it’s just the reality of the disease. I push myself knowing I will pay the price in the next hours, days and weeks to come. I take that pain because It’s worth it to have a taste of the old me sometimes.

I will continue to fight, research and be part of the cure because I am not CRPS. I have learned it doesn’t define me, it is a part of me. I am a CRPS warrior who fights every day and I ask that you help support me and all the others who are suffering from this very misunderstood, debilitating disease. Thank you for taking the time read my story and share in the mission to raise money for continued research and education; to finally find a cure so all CRPS Warriors can go into remission.

All my love, always! I am CRPS Strong!